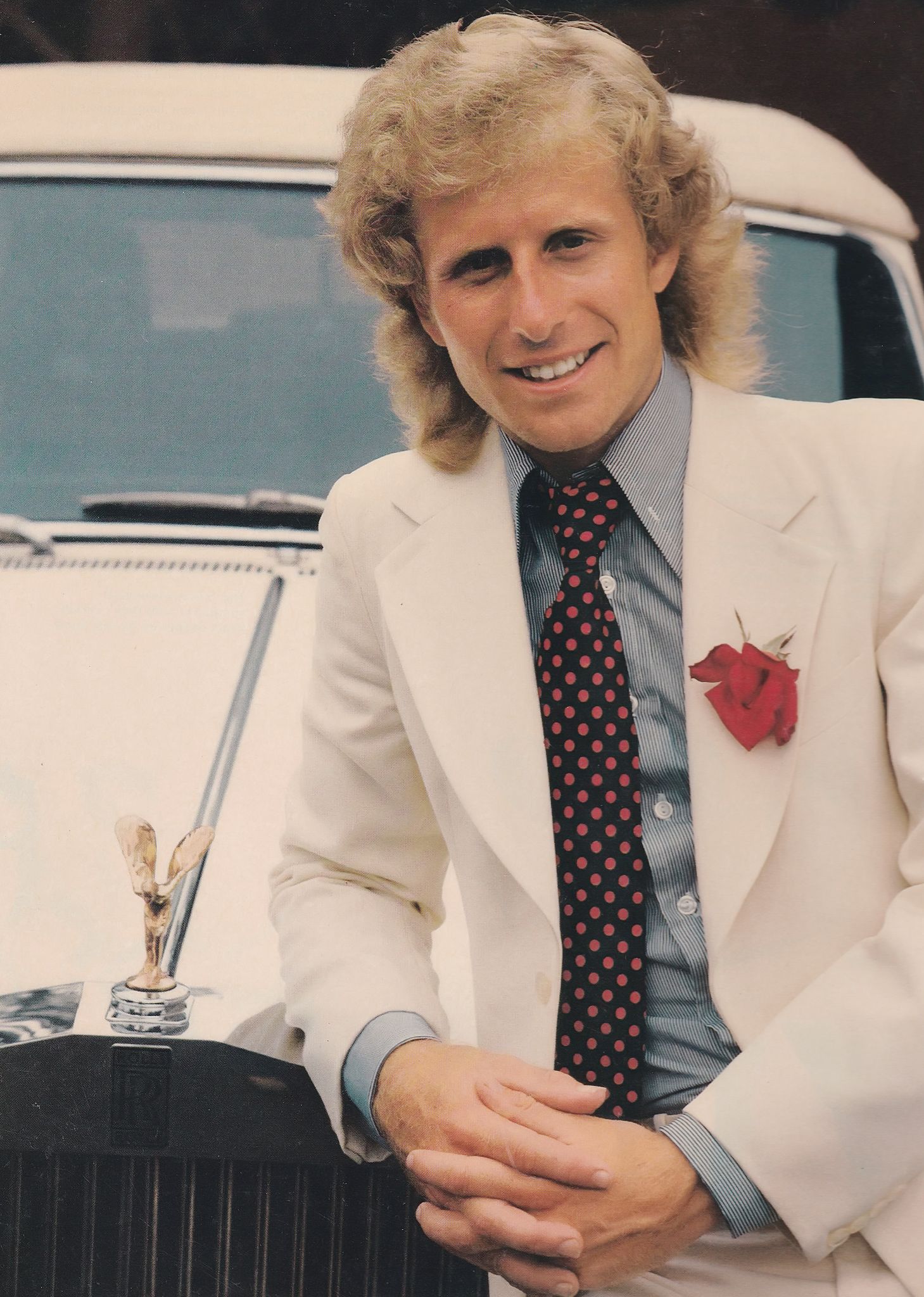

Here is a piece I wrote about John McEnroe in early 2005 that may interest some readers. I originally wrote it for Tennis magazine, but they declined to use it.

I became smitten with John McEnroe the first time I saw him play – the famous 1980 Wimbledon final against Bjorn Borg, in which McEnroe won a wondrous fourth-set tiebreaker but lost the match. It’s the creative genius and the seemingly tortured soul that appeal to me.

I’ve always felt a bond to McEnroe, though sometimes I’ve loathed him and sometimes I’ve loathed myself for having an interest in him that at times has bordered on obsession. I think I share certain core qualities with him, though unfortunately not the tennis playing talent.

On the plus side, I believe we both have incisive intelligence, abundant creativity, quick wit and humor and the capacity for great sensitivity toward others. On the minus side, like McEnroe, I have engaged in self-destructive rebelliousness, expressed senseless anger toward others and at times been ruled by anxiety.

I was 19 when I watched that Wimbledon match and never guessed that I’d end up meeting McEnroe and writing about him. I first thought I’d see him play in person at the US Open in 1986. A financial journalist in New York City, I took a day off work to watch matches the first Friday and was excited to see on the draw sheet after I arrived that McEnroe and Peter Fleming were scheduled to play doubles in the afternoon on the grandstand court.

I planted myself on the grandstand shortly before the previous match finished and was quite pleased to snag the best seat possible with a general admission ticket. But the day ended in disappointment: McEnroe and Fleming got stuck in traffic driving to the Open and were defaulted.

I finally got to see McEnroe live in the 1990 US Open. It was a fourth round match against Spaniard Emilio Sanchez. This time, I went specifically to see McEnroe play. I was still a financial journalist, working for Reuters, and hadn’t written professionally about tennis yet. So there was no chance of securing a press credential. If I wanted a decent seat, I would have to scalp a ticket. I paid $75 to sit in about the 20th row at old Louis Armstrong Stadium.

That was a lot more than I’d ever doled out for a sports ticket before (now I’d consider it an amazing bargain), but I figured for McEnroe, it was worth the price. He won the first set 7-6, and all seemed right with the world. But he lost the next two and exhibited the normal foul behavior he shows when displeased with his play.

I thought: Great, I’ve paid 75 bucks for McEnroe to pull one of his el foldo acts. I felt even worse when I started talking to the guy sitting directly behind me. He appeared quite wealthy — I believe he started a successful bath-sponge company. Yet he didn’t pay one cent for his ticket. He eased my financial pain a bit by sharing his nachos.

And then things really got better. McEnroe came back, playing exquisite tennis that brought back memories of his vintage years. He won the last two sets and had the crowd going bananas the whole time.

I was on a high, feeling a bit euphoric. I decided I deserved more of a reward for my $75 than McEnroe’s victory. I had my Reuters press card and figured a flash of that would gain me entrance to an area where lunch was free.

So I headed over to a building where it looked like food might be served to VIPs and flicked out the ID. Sure enough, the security guard let me right in.

After about three steps in search of food, I saw McEnroe walking right toward me. A jolt of energy went through my body. I said, “Nice match.†He responded, “Thanks,†with a beatific smile. And the need for free food suddenly vanished.

Since 1996, I have been writing about tennis, mostly in my spare time, for publications ranging from Bloomberg News service to this magazine. When McEnroe was scheduled to appear at a group press conference for a senior tour event outside New York City in 1997, I thought that would be a perfect chance to interview him in person for the first time.

I took the afternoon off from my financial reporting job at Bloomberg, rented a car at my own expense and drove out to Purchase, NY. But McEnroe being McEnroe, he skipped the press conference. Still, he had a match to play that evening (doubles with his brother Mark), so I figured I could wait him out. Sure enough, McEnroe showed up about an hour after the press conference ended, and I was the only journalist still around.

So I ended up following McEnroe around for a while, accompanying him as he changed in the locker room, practiced with Tim Wilkison and oversaw his brother Mark’s warm-up (like his two more famous brothers, Mark played tennis at Stanford). McEnroe was quite accommodative in answering all my questions, though he scoffed at my notion that some boxers might make good tennis players. I even told him about paying $75 to watch him beat Sanchez, and he was appreciative. I was in heaven.

I found an excuse to play part of my tape of the interview for a colleague at Bloomberg the next day. He loves the Allman Brothers Band, and while I was talking to McEnroe after his hit with Wilkison, their song “Blue Sky†blared over the court’s speakers. My colleague got a kick out of hearing the interview and the song. And I excitedly wrote my article shortly afterward.

But this story doesn’t have a good ending. The Bloomberg sports editors told me that stories about McEnroe were constantly in the press, so mine was of little value. If I could have interviewed the reclusive Ivan Lendl, they told me, that would have made a story worth printing.

Needless to say, I wasn’t too pleased. I had a feeling the editors were miffed at me over a different issue, and that’s why they didn’t want the story. But in an un-McEnroe like reaction, I bit my tongue and showed respect to the editor who gave me the rejection.

That behavior paid off. Two years later, when McEnroe was elected to the International Tennis Hall of Fame, Bloomberg’s sport editor let me do an audio interview of him. For that one, I took a subway ride to the old tennis bubble on the East River off Wall Street. John invited me on the court to watch him play with brother Patrick before the interview. It was interesting to see the two of them actually picking up their own balls.

One quirk about McEnroe is that he makes scheduling an interview difficult, but once he starts talking, he’s ready to go at length. On this day, I had to get back to the Bloomberg office quickly to resume my regular financial writing work. So I ended up cutting off the interview after 20-30 minutes, though McEnroe appeared game to go longer.

My next extensive interview with him took place in Naples, FL after a senior tour match in early 2001. I had moved to West Palm Beach, FL and convinced the sports editor of The Palm Beach Post, where I worked as a business reporter, to let me write a story about McEnroe. This interview lasted well over an hour and provided a lot of fun give and take.

McEnroe seemed genuinely impressed with my knowledge and insight about him. After the interview, he said, “You have so much, you should write a book.†Without even thinking, I responded, “Yeah, how come I’m not writing your autobiography?†He said with a very friendly tone, “You should.†Alas that was not to be.

The last time I spoke with him was December 2004, at a charity exhibition organized by Andy Roddick in Boca Raton, FL. Some of the tennis was quite good. It was amazing to see McEnroe dominate the court in a doubles match he played with Roddick against Sebastien Grosjean and Aaron Krickstein. But the real highlight for me occurred before any tennis was played.

Despite my previous interviews with McEnroe, his agent informed me he had no interest speaking to me on this day. I was a bit pissed off, thinking: Typical McEnroe, what a jerk.

But then shortly before the tennis began, McEnroe, Roddick and Anna Kournikova lined up in front of the few reporters there, and we were told to go question whomever we wanted. I scurried straight for McEnroe, while all the other reporters went to Roddick and Kournikova.

Lo and behold McEnroe couldn’t have been more welcoming. He stroked my arm and said with a very friendly tone, “Hey, how are…†But I was so juiced up, and perhaps still a little angry at the earlier snub, that I quickly interjected, with a friendly tone of my own, “So, you have a new show lined up?†His CNBC talk show had recently been cancelled.

The rest of the conversation can basically be summarized as “Blah, blah, blah.†But I soon realized I could talk to McEnroe and stare at Kournikova at the same time. She checked me out, checking her out, and I felt all warm and fuzzy.

I thought to myself later, how nice of McEnroe to greet me so warmly. He’d certainly never stroked my arm before. Then I realized the friendly reception may have had nothing to do with McEnroe’s feelings about me. If I hadn’t walked up to him, he would have been standing alone, with both Roddick and Kournikova noticing that no one was interested in talking to him.

So what did I learn from all that transpired from my connection with McEnroe? Probably a comment he made during our talk in Naples summed it up best. McEnroe said words to the effect of “When there’s something you really want to do, don’t ever give up on doing it.â€Â

I don’t know if he was giving the advice to me or himself. But even though the thought is clichéd and obvious, I felt at the time that he had hit on a fundamental truth for me, and I still do.

No tags

![McEnroe[1]](https://www.tennis-prose.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/McEnroe1-300x200.jpg)

Scoop Malinowski · January 26, 2011 at 2:42 am

Very interesting read Dan a lot of Johnny Mac fans will love this. Cool how you were able to tie up all these encounters into an enjoyable feature. It’s always a memorable experience to be around or talk with John McEnroe. Each experience is different. Do you still have that Reuters piece that was never published? That would be a nice story to post as well.