In his two-decade transformation from tennis’ raging rebel to its respected voice of reason, Andre Agassi established a reputation as one of the most charismatic competitors of the Open Era.

He was once the sport’s biggest draw and greatest showman, but one of the most rebellious, reverential and redemptive acts of Andre Agassi’s life came off the court in his career-long quest to transform incarceration into inspiration.

In his autobiography, “Open”, Agassi paints a revealing, compelling, entertaining and sometimes self-serving portrait of an ex-champ as ex-con.

The book is much more than Agassi’s admission of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, but fright and hate are as central to this story as mom and dad and forehand and backhand.

Early excerpts of the book that detailed the salacious drug story detailing how Agassi began using crystal meth in 1997 may have suggested a tennis version of sex, drugs and Barbra Streisand torch songs, but this book is much deeper than that.

It’s a multi-layered story that chronicles both Agassi’s rise as a champion, his search to seek out his identity, his efforts to form a surrogate family to supplant his biological one and ultimately how one man survived two decades of what he describes as deep hate  a loathing of tennis and what it represented in his life  and found redemption in love.

Perhaps Agassi spends so much time chronicling his hate to highlight the redemptive powers of love  his love for trainer Gil Reyes, who became the father he desperately sought (a “life guardâ€Â), his love for Steffi Graf, who represents the substantive real love after a marriage to actress Brooke Shields that Agassi suggests was as genuine as a sitcom set and his love for the emotional and intellectual healing properties of education.

Agassi’s ability to time the tennis ball with all the accuracy of a stop watch helped him make history as one of only six men in tennis history to win all four majors. The book is Agassi’s admission that he’s been doing time in tennis ever since he first picked up a racquet.

During his Grand Slam glory days, Agassi was prone to positioning ball kids as if they were lookouts on his latest competitive caper. Agassi did more than play tennis, he turned major matches into Grand Slam larceny in stealing strength from opponents’ legs with crisp cross-court combinations, pilfering their power by ripping shots on the rise and robbing their resolve by forcing them into states of retreat.

There was a thief motif to the way Agassi played the sport and a central theme of “Open” is that Agassi was sentenced to a life he never chose.

The sound of the bouncing ball comes across as stark as the sound of cell doors slammed shut as Agassi served hard time in his personal prison that is the tennis court, trying to perform to external expectations placed upon him by a demanding dad, cash-strapped coach and misunderstanding media, all of whom projected a persona upon him that was as welcome as a summer of weekends on Riker’s Island.

Fear is a force more powerful than Agassi’s vaunted return and fear  fear of reprisal from his father for failure to fulfill his tennis dreams, fear of being stranded at an Academy he wants so desperately to escape, fear of conforming to the identity imposed on him by others and fear of what his life would be if he ever walked away from the only occupation he ever knew  imposes paralyzing pressure on the young Agassi.

If you think that’s hyperbole, read the book.

The language of lockdown is pervasive from the beginning as Agassi calls the court constructed in his Las Vegas backyard “My prison.†He portrays his domineering dad, Mike, as a volatile and sometime violent guard, who confronts daily life armed with an arsenal of weapons ranging from a gun his son says his father pulls on a passing motorist over a traffic dispute, an ax handle he keeps in his car, a handful of salt and pepper in each pocket as allies to blind potential foes in sudden street fights and his fast hands that made him a two-time Olympic boxer for his native Iran and which he later deploys to knock a truck driver unconscious in a street fight that punctuates a road rage incident.

Mr. Agassi is presented as a man always on the edge of erupting in rage, while his youngest child with the wide eyes and bowl haircut tries to keep the peace by playing ball and keeping pace with “The Dragonâ€Â, the high-powered Prince ball machine Mr. Agassi builds to spit out shots in excess of 100 mph, all to keep “Pops†satisfied.

The relationship between domineering dad and dutiful son seeking to please is one of the central themes the book. At times, the dueling disparity between the two seems almost too trite  as if it is a life-long rally of hope and dread between a martyr and madman staged over an ever-expanding emotional barrier rather than a net.

Mike Agassi is portrayed as a demanding dad driven to extract excellence from his son like a man tapping blood from a vein to fulfill the American dream and erase the frustration of his own failed boxing career that saw him use a toilet to aid his escape route from a Madison Square Garden bathroom moments before the opening bell of his scheduled prime-time boxing match at the World’s Most Famous Arena. That image of the elder Agassi shaking in the dressing room at the thought of fighting a bigger, tougher foe and sneaking out of the bathroom instead of facing his own dragon in the ring is the first in a series of confinement and escape scenes that appear throughout the book.

“I know I have a reputation,” Mike Agassi wrote in his 2004 memoir The Agassi Story. “People say I’m abrasive. Domineering. Fanatical. Overbearing. Obnoxious. Temperamental. Aggressive…People say I pushed my kids too hard, that I nearly destroyed them. And you know what? They’re right. I was too hard on them. I made them feel like what they did was never good enough. But after the childhood I had, fighting for every scrap in Iran, I was determined to give my kids a better life. I pushed my kids because I loved them.”

In one sense you can read the book as Agassi’s journey to find a father figure extending compassion rather than condemnation for his failings. On the other hand, his portrayal of father whose approach to problem solving is a fist to the face and a mother, Betty, whom the book suggests is more interested in solving jigsaw puzzles than uniting her fractured family, reveals Agassi as a man almost shamed by his family and in those instances his immediate family members can come off more as parody than as people.

In a 2004 interview with Tennis Week, Mr. Agassi said his son had never read his book, “The Agassi Story”, or knew much about his life. He suggested his impoverished childhood in Tehran where he shared a single room with his mother, father, three brothers and a sister in a home that lacked electricity, running water and a dinner table as the family ate on a dirt floor shaped the desperate desire for success that fueled the inferno of intensity he displayed with his son. Agassi said in an interview last week his father has not read his book either.

Reading “Open” it is clear the disconnect between father and son still exists and you wonder if, instead of agreeing to read each other’s accounts of life under the same roof, they’d be better off sitting down over a beer and talking out their differences while there’s still time to do so.

The common link that connects nearly all of the people in Agassi’s adolescent life is that all are damaged or suffering in some way: older brother Philly confides he is going bald “he says this in the same way he would tell me the doctor has given him four weeks to live,†Andre writes; best friend Perry Rogers has a cleft palate, his father is presented as an emotional cripple unable to even embrace his son after he returns home from one tournament, his mother, the daughter of an English teacher, consoles her son by pointing out the positives: at least dad hasn’t killed anyone yet or wound up in jail.

The characters in Agassi’s autobiography are memorable, but it is his long-time view of the court as a cage that is even more unforgettable and unsettling.

“Suddenly my father had his backyard tennis court, which meant I had my prison,” Agassi writes on page 33 of the book. “I’d helped feed the chain gang that built my cell. I’d helped measure and paint the white lines that would confine me. Why did I do this? I had no choice. The reason I do everything.”

The white lines on court are figurative bars on the cell and those lines extend to Agassi’s childhood bedroom where his older brother and cellmate, Philly, the eldest of the four Agassi children dubbed “a born loser” by the unforgiving family patriarch, paints a white line down the center of the room “dividing it into his side and mine, ad court and deuce,” Agassi writes.

Shipped off to the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Bradenton, Florida, after his father sees a 60 Minutes expose on Bollettieri, Agassi’s initial impression of the place is that he’s been transferred from home confinement to penitentiary for players.

“(The Bollettieri Academy) is nothing fancy, just a few outbuildings that look like cell blocks,” Agassi writes on page 73. “They’re named like cell blocks too: B Building, C Building. I look around, half expecting to find a guard tower and razor wire.”

Instead he finds row after row of tennis courts and though the young Agassi consoles himself with the fact his father could only afford three months tuition, Bollettieri, bedazzled by the kid’s brilliant strokes and blindingly fast hands, tears up his father’s check in granting the teenager a free scholarship.

It’s an act some coach-starved kids might view with appreciation  see Pancho Segura escaping from the slums of Ecuador and landing in New York City virtually penniless and unable to speak English but still committed to pursuing the tennis dream; or Mansour Bahrami, who learned to play with a dust pan as a racquet and a rolled up piece of tape as a ball looking over his shoulder for fear he might get shot playing tennis amid a repressive regime in his native Iran; or Younes El Aynaoui who served as a bus driver and janitor for Bollettieri’s Academy to pay his own tuition  but then those players chose tennis as their passion.

It is an act Agassi, who feels pushed and prodded into the sport like a marionette serving a multitude of masters on match day, views with all the enthusiasm of a juvenile facing furlough only to see his sentence extended.

“The warden has tacked several years to my sentence, and there’s nothing to be done but pick up my hammer and return to the rock pile,” Agassi writes on page 77 of the book.

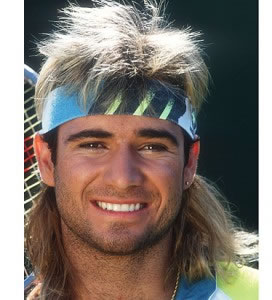

Even his trademark shoulder-length, two-toned mullet, which Agassi later enhances with a hair piece when his long locks start to fall out, is described as a ball and chain that makes him a slave to image.

Make no mistake, in collaborating with “The Tender Bar†author J.R. Moehringer, Agassi has created a beautifully written book with sharp observations, detailed descriptions and pointed dialogue delivered in the present-tense which effectively puts you side-by-side with the eight-time Grand Slam champion as he journeys through a life that saw him seize international stardom as a teenager.

It is far more revealing than recent autobiographies from Pete Sampras (Agassi actually mentions Sampras’ first girlfriend, DeLaina Mulcahy, while Sampras himself omits her from his book) and Serena Williams in that Agassi has the guts to open up about his closest relationships, the internal struggle he fights in trying to establish his own identity and his deep contempt toward tennis. But at times the repeated use of the prison metaphor  combined with his consistent chorus of “I hate tennis”  comes perilously close to painting Agassi as a man with a persecution complex or Oliver Twist with a tennis racquet (in a Dickensian device, Agassi recalls the food in Bradenton as “gruel”).

Agassi is a prized prodigy who reveals himself to be a sensitive soul, yet at times the story is so slanted toward imposing the strict view of the tennis court as a form of Hades reconfigured as a rectangle dissected by a net, the protagonist can come off prone to periods of self-pity. It’s possible that angle of the story is more pronounced to highlight the dramatic rise from victim to victor, but Agassi’s story is compelling enough without the dogged determination of accentuating the tennis as detention theme.

It is completely understandable that a kid ripped out of his own home just as he is developing meaningful relationships and shipped thousands of miles away to be trained like some sort of tennis thoroughbred would experience resentment and outright hatred toward the game he was forced to play. The relative absence of the adventurous, spirited and at times joyful competitor Agassi was at times in his career creates a bleak climate  the teenager sporting the wild hair and lava-colored spandex under denim shorts brought color to the court, but Agassi writes of his life in shades of morose monochrome.

Throughout the book, Agassi takes almost perverse pleasure in informing friends, confidantes, coaches and celebrities, including Kevin Costner, of his secret: “I hate tennis.” Though he maintains a public posture that he loves the game  confessing he consistently lied to the media, including a nationally-televised interview with Charlie Rose  Agassi steadfastly sticks to his story that deep down he despised the game.

To be sure, many elite athletes have acknowledged a love-hate relationship with their sport. In fact, Hall of Famer Maureen “Little Mo†Connolly, the first female to ever sweep the Grand Slam, confessed to cultivating a hatred for opponents in her 1957 autobiography Forehand Drive.

“I hated my opponents. This was no passing dislike, but a powerful and consuming hate,” Connolly wrote in her biography. “I believed I could not win without hatred. And win I must, because I was afraid to lose. The fear I knew was the clutching kind you can almost taste and smell. This hate, this fear became the fuel of my obsession to win.”

Little Mo, like Agassi more than four decades later, eventually comes to the realization that only by tapping into love can she truly play inspired tennis and live a fulfilled life.

In his autobiography, “You Cannot Be Serious”, John McEnroe wrote about how tennis was one of his least favorite sports, but he pursued it because it was the sport he was best at. The contrast is that while serve-and-volleyer McEnroe has subverted his image as tennis’ angry young man with commercial parodies playing off his trademark “You cannot be serious!” rant, in effect turning traded mark anger into comic commercialization; returner Agassi rejects his image as a fun-loving tennis rebel by spending so much of his story focusing on the pain the game provoked in him. At times, it feels like he’s ripping the scab off a wound and rubbing it raw to try to show you how it felt.

It’s admirable Agassi Opens up, you just wish he’d lighten up at times, too.

Where is the Agassi who would serenade fans with his smile? Where is the guy who would dare to hit a between the legs shot then bow dramatically at the adoring crowd’s response? Where is the Agassi who tried to bring a bit of levity to a contentious 1992 Davis Cup doubles match between the USA and Switzerland by screaming from his court-side seat at an irate McEnroe “The question! Answer the question!” Where is the Agassi, old friend Luke Jensen recalls throwing water balloons at practice, trying to hit dimes place on the court, the Agassi who would pull up to the Taco Bell drive thru and be forced to raise the doors of his gull-winged Lamborghini because the food wouldn’t fit through the window?

Having watched Agassi play throughout his career and listened to his often insightful press conferences, it’s just difficult to imagine he truly viewed tennis in such black-and-white terms for so much of his career. In that sense, the hate angle can come off as contrived at times and dulls what is intended to be the sharp edge of the learning curve of life.

Obviously, we all tell the truth on our terms and in so doing sometimes create our own reality, but in so strictly adhering to the “tennis is a prison and I hate it” theme Agassi limits the gradations of the growth process and we’re left at times wondering if that insistence is more literary device than literal truth.

The prison analogy becomes particularly tough to swallow when Agassi recounts meeting Nelson Mandela, whose own memoir movingly described the brutality he was subject to in a real prison, and who tells Agassi he spent time playing tennis on a crude court to escape his very real prison. The meeting with Mandela helps Agassi put his own life into perspective as Agassi begins to accept responsibility for his own shortcomings rather than assigning them solely to his father, Nick Bollettieri, his friend/drug buddy Slim.

The former convict of tennis sees himself as a criminal complicit in building his prison and resolves to help bail others out of their incarceration of ignorance.

“For the first time in many years I’m acutely aware of my lack of education,” Agassi writes. “I feel the weight of this lack, the misfortune of it. I see it as a crime in which I’ve been complicit. I think of how many thousands in my hometown are victims of this crime right now, deprived of an education, unaware of how much they’re losing.”

At times, Agassi can be so convincing in conveying his inner torment emanating from the tennis court as a torture chamber that he provokes you to ponder the notion that immeasurable fame, fortune, loyal friends and a former model wife don’t give you immunity to imprisonment, they merely make the cell you call home a bit more luxurious and far less dangerous than one in a real penitentiary.

Like so many of us, Agassi is a bundle of contradictions that coexist as closely as strings in a tightly-wound racquet and he is mainly effective in exploring those disparate degrees of his personality.

Agassi reveals himself to be an eighth-grade drop-out who hates school yet grows into a philanthropist who so values education he eventually builds his own charter school; a showman on court seeking substance off it; a man who becomes a devoted fitness fanatic under the guidance of gentle giant Reyes yet never loses his appetite for fast food and has an affinity for washing down sleeping pills with vodka; a sensitive soul so moved by a New York City restaurant manager’s concern over scrimping for his children’s college education he gives the man some of his Nike stock, yet a competitor who could be so crass and cranky he was defaulted from a tournament for repeatedly verbally assaulting a linesman as a “coâ€â€suckerâ€Â; a spiritual seeker who developed a firm friendship with a Las Vegas preacher turned musician, John Parenti, yet an acidic cynic who ridicules Michael Chang’s repeated references to Jesus as absurdly self-centered; a competitor so fierce he vomits on the court during the D.C. final against Stefan Edberg and is so dazed the ball becomes a blur, yet a man who freely admits he tanked a match against Chang because he doesn’t have the stomach to battle despised nemesis Boris Becker in the final; a man who feels trapped and misrepresented by the “Image Is Everything” tag line he’s required to utter during a Canon television commercial, yet a young man who goes on to don the hairpiece because he’s afraid of betraying that image; a man who rails against the media misrepresentations yet perpetuates them by repeatedly lying to the media in his press conferences.

Pointing out the difference between himself and Sampras after they conducted a combined interview, Agassi says his Southern California rival has all the personality of his pet parrot, Peaches. “At least when I bullshit a reporter, I do it with some flair, a little color,” Agassi writes on page 184. “Pete sounds more robotic than Peaches.â€ÂIt’s one thing for Agassi to basically brand Sampras, a man who earned more than $43 million in prize money, a tightwad after a valet at an Indian Wells restaurant confides to Agassi and Gilbert that Sampras tipped him all of $1 (in a move that might even make Ebenezer Scrooge cringe, the valet claims Sampras told him to give the $1 to the person who actually pulled his car around to the door). But the level of antipathy between arch rivals is even more revealing in Agassi’s interpretation of Sampras’ smile and pat on the back at the conclusion of their 2002 US Open final. “Pete gives me a smile, a pat on the back, but the expression on his face is unmistakable. I’ve seen it before. Here’s a buck, kid. Bring my car around,” Agassi writes in revealing his vision of that iconic image of two of the greatest American champions in history sharing an embrace at net that was really one champion’s condescending smile after extending his Grand Slam final superiority over his rival.Give Agassi credit though, for not pulling any punches when it comes to his characterizations of his foes.

Agassi is so pointed in his descriptions of fellow players you might find yourself wishing he’d shorten the book tour and join the broadcast booth.

Of Sjeng Schalken he writes: “He’s 6-5, but serves like he’s 5-6.”

Of tanking an Australian Open match to Michael Chang he writes: “Congratulations, Chang. I hope you and your Messiah will be very happy.”

Of the difference in his rivalries with Sampras and Patrick Rafter he writes: “I always thought Rafter and I made a better rivalry, aesthetically, because Rafter is more consistent. Pete can play a lousy thirty-eight minutes, then one lights-out minute and win the set, whereas Rafter plays well all the time. He’s six foot two with a low center of gravity and he can change direction like a sports car.”

Of Sampras’ single-minded approach to tennis, Agassi writes: “I envy Pete’s dullness. I wish I could emulate his spectacular lack of inspiration, and his peculiar lack of need for inspiration.”

Agassi recounts his 1995 season he calls his “Summer of Revenge” including his four-set US Open semifinal win over Becker in which the bad blood built to a boiling point.

“Before we take the court, as Becker and I stand in the tunnel, I tell the security guard, James: ‘Keep us apart. I don’t want to see this fu–ing German in my sight,” Agassi writes in “Openâ€Â. “Trust me, James, you don’t want me to see him.”

After Agassi completed a four-set win over Becker, he took his time walking to net leaving Becker to stand alone waiting for the post-match handshake. Agassi writes: “I leave him standing there like a Jehovah’s Witness on my doorstep.”

Whether you agree with Agassi’s assessments of his opponents or not, it is fascinating to read his descriptions, which are often so sharp he gives you a glimpse of what he was thinking and feeling on court. He effectively forces you to confront the competitive chill and internal rage he felt and in so doing wrenches readers out of their seats and thrusts them into the competitive cauldron.

Much has been made of Agassi’s admission that he used crystal meth for much of the 1997 season.

The fact that a future Hall of Famer who left the game with a well-earned reputation polished to near pristine state has the guts to admit to drug use that could potentially damage his image is admirable and could serve as an inspiration to others who have flirted with drug use. Undoubtedly, it will also help spike sales of the book as some readers will relate to the dirt details and others will revel in seeing the depth of Agassi’s depression that saw him bottom out in drug use before beginning one of the most remarkable career resurrections in Open Era tennis. Clearly, that part of the story serves the book several levels. It also reinforces the old life lesson that “there’s no shame in falling down, the shame is in not getting up when you fall.”

That the inmate would seek asylum in crystal meth comes as no surprise when you read Agassi’s account of his early indoctrination into drugs and booze.

Agassi suggests his father feeds him a white pill, suspected to be speed, during a junior national tournament in Chicago; is awarded his first beer  a cold Foster’s Lager  at age 12 by a junior coach after winning a tournament in Adelaide, Australia; graduates to smoking weed and drinking “gallons†of Jack Daniels at the Bollettieri Academy and numbs the pain of his personal life by occasionally swallowing sleeping pills he chases down with Vodka prior to the start of long plane rides.

Agassi admits he did crystal meth, tested positive for the drug then lied to the ATP about it and benefited when his positive test was covered up. But if the book is accurate, it seems he was self-medicating to a degree long before he snorted his first line of meth.

The meth revelation is less than one chapter in the story and while it took courage for Agassi to be so Open about it  there is some speculation Agassi’s former best friend and ex-manager Perry Rogers, with whom he had a falling out (Rogers sued Graf last year), knew all of the dirty drug details and may have been tempted to disclose them and if that’s true then in essence Agassi beats Rogers to the punch and takes control of his own story in outing himself as a former drug user  the fact that he does not disclose how he kicked a highly-addictive drug like meth (there is no mention of rehab or even counseling) does detract from the power of the story as a teaching tool. Had Agassi been clear in exactly how he got off the drug and the lesson he learned as a result  he has spoken of his second career as his effort for “atonement† that part of the story would resonate more than it does now. As it is written, it feels incomplete  as if there is more to that story than he’s telling here.

In response to Martina Navratilova’s criticism of his lying about drug use, Agassi asked for compassion rather than condemnation and he is absolutely right in doing so. Yet, genuine compassion is not something to be doled out selectively like appearance fees to stars. And the while it is admirable many have expressed compassion for Agassi’s plight of pain it makes you wonder: where is the compassion for Xavier Malisse or Yanina Wickmayer? Both Belgians were hit with one-year suspensions for missing drug tests, neither has ever tested positive for a banned substance, while Agassi walked 12 years ago after lying about his drug use and did not miss a day of play? Is that tennis’ version of compassion where ranking and status essentially gives you the immunity of a get out of jail free card and no one seems to car much about the lower-ranked players tossed aside on the tennis trash heap?

Agassi is open in covering both his relationship and break-up with actress Brooke Shields and his courtship with Graf. Though after spending more than 100 pages with the superficial Shields (who can come off as so controlling and image conscious she actually asks Agassi to re-enact his marriage proposal) you might find yourself wishing the authors got to Agassi’s wooing of Graf faster.

The charm of that courtship comes through from the very beginning when Agassi’s coach, Brad Gilbert arranges for him to hit with Graf in Miami. Later, when Agassi sends Graf, who is still dating her boyfriend of six years, red roses, you feel his pain when he peers out of his hotel room window and sees Graf has relegated the roses to the patio.

The book succeeds most in detailing Agassi embracing his true father figure, trainer Reyes, who becomes a “life guard” in not only building Agassi’s body, but his mind as well. It is ultimately this tennis outsider who empowers Agassi by showing him that even if he hates the sport he can still use the public platform he’s attained to achieve good and productive things.

Interestingly, Agassi’s tennis epiphany comes with the help of both coach Brad Gilbert and Reyes. When Agassi chokes severely for the first two sets of the 1999 French Open final vs. Andrei Medvedev it is Gilbert who sheds his image as the comical, common sense coach whose approach to breaking down the process of playing into executing essential components extends to the way he orders chicken parm (Gilbert insists on order the chicken, parm and sauce separately) and rips into his charge with a fury at seeing him wallow in self-pity in the locker room during a rain delay.

Gilbert, who Agassi says had never even raised his voice to him before, seems to channel Vince Lombardi and Rocky’s corner man Mickey in taking the gloves off and railing in rage at Agassi blowing his dream of completing the career Grand Slam.

“If you’re going to lose at least lose on your terms. Hit the fuâ€â€ing ball,†Gilbert tells Agassi in the locker room. “And if you’re not sure where to hit it, here’s an idea. Just hit it to the same place he hits it. If he hits a backhand crosscourt, you hit a backhand crosscourt. Just hit yours better…The last 13 days I’ve seen you lay it on the line. I’ve seen you rip it, under pressure, maim guys. So please stop feeling sorry for yourself and stop telling me he’s too good and for the love of God, stop trying to be perfect!…If you’re going to go down, OK, go down, but go down with guns blazing. Always, always always go down with guns blaaazing!â€Â

Gilbert punctuates that motivational speech slamming the steel door to the locker room shut leaving Agassi to consider the advice and then go out and face the fire and tame the tournament he calls “The dragon.”

It is the turning point to that match and in a sense serves as a springboard to the change Agassi adopts in life. He stops whining and starts winning, stops stressing and starts playing, stops feeling sorry for himself and starts putting his passion to work for himself and for others.

One of the most potent messages of the book is that an eighth-grade dropout realizes that real answers can only come from asking yourself the toughest questions.

Certainly, there are incomplete elements to the book: in addition to failing to detail how he got off drugs, Agassi does not discuss the professional and personal break-up he endured with former best-friend and ex-manager Rogers leaving one to wonder if Rogers is working on his own version of events. Another minor quibble is how could publisher Knopf release a book about one of the most famous and photographed American champions in history without including a section of glossy color photos presenting Agassi’s transformation as a player and a person? The black-and-white photos in the book are tolerable, but come off as a bit cheesy compared to Agassi’s full-color revelations. Hopefully, the publisher will rectify that problem with the paperback edition is printed.

All in all this is a compelling autobiography and worth reading.

The true triumph of Agassi’s life story  and this book  is that ignorance is the ultimate form of imprisonment and education is the only escape. And in writing this book and building his own charter school and reinventing himself from a perceived punk to a productive philanthropist, Agassi has pulled off one of the greatest tennis escapes of all.

No tags

Dan Markowitz · June 12, 2010 at 2:54 am

Rich,

You’ve succeeded in writing a review longer than the book. Wow! Dude, what did you read “Open” with a magnifying glass? I’m impressed. But you didn’t mention the most important part of the book. How Agassi says when he lost to Vince in the Rd. of 16 of the Aussie Open that he could’ve beaten Vince with a frying pan.

Sid Bachrach · June 13, 2010 at 4:11 am

RP, Great to have you back and in fine writing form as usual. I loved Andre’s book. However, he seems to stretch the truth on a few occasions. He tells a story about how Jeff Tarango cheated him out of a juniors match years ago. Tarango said Andre made it all up, that they were never even in the same tournament when Andre says it happened. Tarango says the records from those junior tournaments are still around somewhere and Andre is in no hurry to examine them. Then there is Andre’s assertion that when threatening letters were sent to Brooke Shields with an address on them, Gil Reyes would go pay a visit to the jerks who sent the letters and these people would go away. I find it hard to believe that Gil Reyes would take the law into his own hands and go on some viglilante missions and never get caught or arrested. That story, whether concocted by Andre or Mohrenger, is sheer fiction.

The story about Pete giving the guy who retrieved his car a one dollar tip is absurd. Andre claims that he and another guy made a bet about what Pete’s tip would be and the parking attendant confirmed Pete just left a dollar. Andre obviously did not make a bet at the time. Who does that? It makes good reading but it never happened.

Richard Pagliaro · June 13, 2010 at 12:48 pm

Sid:

Thank you. And you make excellent points. Another story I have a hard time believing is the story that his dad, Mike Agassi, pulled a gun on another motorist after a traffic dispute. A friend of mine knows Mike Agassi (has known him for years) I asked him to verify that story. Mike, according to my friend, says that never happened. Says he never pulled a gun on anyone. I also find it hard to believe Mr. Agassi and Mr. Graf nearly came to blows.

Dan Markowitz · June 13, 2010 at 11:09 pm

Wow, Rich, your questioning Agassi’s veracity? How shocking. I think Andre was way off in saying in the book that it was Brad Gilbert who broke off their coaching-player relationship. Why would Gilbert give up such a high-paying job and one where he established credentials at the time as being the best coach in tennis. I think Andre should’ve entitled his book, “Open and Closed,” as he clearly addressed the things he wanted to address and in his own eyes. But it’s a myth that non-fiction books, all of them, not just Agassi’s, are objectively factual.

Richard Pagliaro · June 14, 2010 at 1:54 pm

I’ve been told a very intersting story from another coach on why the AA-Gilbert partnership broke up. I do not know if it’s true and definitely cannot post it becuase of the content and because I have no idea if it is true or just speculation but it is a very interesting theory.

YEs, if Tarango ever writes a book he has a lot of interesting things to say about AA.

When it comes to athletes’ autobiographies, I’m always reminded of the Charles Barkley line when he was asked about a story in his book and Barkley replied: “I don’t know, I haven’t read it yet.”

Scoop Malinowski · June 14, 2010 at 3:02 pm

Heard Spadea said the same thing about “Break Point”

Dan Markowitz · June 14, 2010 at 4:33 pm

Spadea wouldn’t have admitted that. He said he’d only read one book after high school and that was the Kama Sutra.

Rich, if it’s theoretical, why not print it? We’re all about theories here at tennis-prose.com.

A Tarango book, for whom to read, Tarango and his family. Hey “Break Point” sold the 7,000+ books it did, and it would’ve sold more if publisher of paperback didn’t go bankrupt, because it was entertaining, but also because Spadea was #19 in the world when he started writing the book. When he ended, he was #78, but he was still on tour, in the thick of things. I don’t think even Jim Courier, even if he was going to talk honestly, could sell a book with a big publisher now. Michael Chang couldn’t. I heard Justin Gimelstob say he wanted to write a book. I haven’t heard of any takers. Corina Moriaru had an inspiring story, but has she sold 1,000 copies? Probably not.

Dobey · June 14, 2010 at 8:29 pm

Hey RP! It’s me, Dobey, back from the tennis week days. I missed your great columns although I did see you on the tennis channel a few times. I loved Andre’s book. He had a gifted writer help him and that imroved the book immensely. I thought Pete Sampras’s book was a snoozefest. To add to what Sid and you both said about some of the tall tales in the book, I have my doubts about Andre’s story of taking football legend Jim Brown to the cleaners when Andre was about 10. I have no doubt that at age ten, Andre would have handily defeated Jim Brown in a tennis set, given Andre’s genious at an early age and given that Jim Brown was a football player, not a pro tennis player and Jim would have been about 47 years old at the time. But the story about how Andre and his dad hustled Jim Brown out of some pretty serious dollars strikes me as absurd. How come we never heard about this until Andre’s book comes out? I would like to hear Jim Brown’s take on this story. I doubt that Jim Brown ever was in the business of making bets against ten year olds. I doubt that any tennis club would allow ten year olds to be in the business of playing tennis against 47 year olds for prize money. I wonder if Andre’s dad was so callous as to use a ten year old as a stalking horse. I would like to hear Mike Agassi and Jim Brown give us their take on this.

On the tennis side of the book, I would like to have read Andre’s take on his matches with Gustavo Kuerten. Kuerten matched up pretty well against Andre and in Lisbon, Guga managed to defeat both Andre and Pete. Andre has so much to say about Chang, Sampras and Becker, most of it negative, but he never discusses his matches with Kuerten.

vinko · June 14, 2010 at 8:50 pm

I wish Tennis Channel would stop running that Longines ad for a while. I am sure the school does fine things but they run that ad every five minutes. It’s gotten to the point where you just can’t take it anymore.

Dan Markowitz · June 14, 2010 at 9:20 pm

vinko and dobey,

Good to see you up on the boards again. How did you find tennis-prose.com? I think you both make very good points. Jim Brown playing Andre for big money at 10 sounds fishy, but I do know that Brown, who considered himself a great basketball player, once challenged the old Knick guard, Dick Barnett, to a game of one-on-one.

And Vinko, absolutely, I can’t watch that Longines commercial anymore. Even though Andre and Steffi, I can’t call her Stefani either, are so cute and convincing in it.

I liked “Open,” but as I stated when we blogged about it on the old TW site, I’m looking forward to Brooke Shields book and any other people who were flogged by Andre, including his dear old dad, to come forth and dispute the “open-ness” of Agassi’s assertions. I know for a fact that Spadea says when he practiced with Agassi during the time Agassi says he could’ve beaten Vince with a frying pan, the practice matches were very close, and of course, Vince beat him in big matches both in Cincy and Aussie Open, too.

Scoop Malinowski · June 14, 2010 at 9:45 pm

Wow, it’s great to have the legendary tennisweek tennis talkers Vinko and Dobey here at tennis-prose.com! Hope you guys like the site and help make it better. Agree about those Longines commercials, talk about overKILL. They should have made a second totally different commercial to contrast it. Jim Brown was in NYC at Bob Arum’s Friar Club night two weeks ago, wish I went and asked him about it! Agree with Dobey, no way would a guy like Jim Brown be making bets playing tennis with a ten-year-old twerp kid. AA has got some imagination.

vinko · June 15, 2010 at 3:28 am

I saw a reference to tennis prose on twitter. Had I logged on there an hour later I would have missed it.What a pleasant discovery. Speaking of Andre his empty pockets ridicule of Pete Sampras was in poor taste. How does Andre know what Pete donates to charity?

Dan Markowitz · June 15, 2010 at 12:36 pm

Wow, we’ve reached Twitter. We’ve hit the big time folks. Vinko, you’re a five-tool technology guy. I think with Agassi and Sampras, Andre knows Pete bested him on the tennis court so Andre has to emphasize that he’s bested him on the compassion and philanthropy side. There’s always been an edge to Agassi, a short guy complex, even though he’s not that short, that Pete never harbored.

dobey · June 15, 2010 at 4:53 pm

Hey Scoop, great to be back with you and RP et al. I found tennis-prose through a European tennis web site called GVtennisnews. It’s a pretty neat tennis site with European emphasis and they have a twitter site also. The GVtennis news twitter site gave the URL for tennis-prose and said it’s “an interesting new tennis web site”. So that is where I found it! Nothing against http://www.tennis.com but it is kind of dull!

Sid Bachrach · June 16, 2010 at 5:02 am

To add to what Dobey and others said about Andre’s assertion that he took Jim Brown to the cleaners when Andre was 10 years old, I would add the following skepticism to Andre’s account. If Mike Agassi actually forced 9 and 10 year old Andre to play money matches in which the Agassi family used the winnings for family expenses, that would be a form of child abuse. No 10 year old should be forced into this pressure cooker of an environment. I doubt that Mike Agassi would have done such a thing. I think I can say with certainty that Jim Brown would want nothing to do with any such cruel misuse of a child by a parent. I doubt that Jim Brown would ever try to hustle a ten year old child. Jim Brown has spent most of his years after football working with troubled kids. The idea that he would play a high stakes tennis match with a ten year old strikes me as sheer fantasy. Third, Jim Brown would not fall for such a hustle. If Mike Agassi were pushing Jim Brown into putting thousands of dollars on a tennis match against Mike Agassi’s ten year old son, Jim Brown would smell a rat. Jim Brown would know that Mike Agassi was trying to pull off a hustle on him and that Andre was a ringer. Mr. Brown would want no part of that.

I would like to hear Jim Brown’s take on Andre’s tall tale.

Richard Pagliaro · June 16, 2010 at 11:57 am

Hey Dobey, Vinko – Great to see you!!! Thanks for checking in. Now all we need is DMan for a full fledged reunion 🙂

I thikn I mentioned it earlier but a friend of mine has known Mike Agassi for years and says he flatly disputes the account in the book that claims he pulled a gun on a motorist. Says that absolutely did not happen and he also told me “think about it: someone pulls a gun on you you’re going to get the license plate and report the guy to the police before he kills someone….”

I tend to question the story where Mike Agassi and Peter Graf reportedly almost came to blows. Just can’t see that happening at their age. Also, I’ve met Mike Agassi and have interviewed him and the book claims they almost came to blows arguing over the two-handed backhand. But Mike Agassi himself plays with a one-handed backhand and he told me he’s always liked seeing the one-handed backhand so why on earth would he nearly get into a brawl over a shot he himself plays with? Doesn’t make sense to me.

Dan Markowitz · June 16, 2010 at 1:10 pm

What about Tommyboy, Hairload, the guy from Texas who knew what he was talking about, and James Himself?

I can totally believe the Jim Brown story. When Andre was 10, Brown was around 40, still a physical specimen and outrageously competitive. I’ve heard a story where at a party in LA he challenged Dick Barnett of the Knicks to a one-on-one game and I can imagine money was bet on the game. Jim Brown was no choir boy and he was an all-American lacrosse player in college at Syracuse. He considered himself the best athlete in the world and I can see that match between the boy Agassi and Brown taking place with high stakes on it.

I don’t know about the gun story, but Mike Agassi was clearly a bully and a violent, agitated man. It’s amazing sometimes when you meet a man when he’s 70 and you say, “The stories of this guy being a complete monster when he was younger have to be false,” but a lot of mellowing can take place in the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s. This was Las Vegas in the 1970’s, an outlaw town, I could see Mike Agassi pulling that gun.

The two-handed backhand was the way to go in the 70’s, Connors, Borg, Evert. Why would Mike teach Andre a one-hander? It’s not like Mike was a great player. He wasn’t trying to wean another Mike Agassi tennis player.

Sid Bachrach · June 16, 2010 at 3:32 pm

Andre has a riveting account of his hate filled match at the US Open with Boris Becker in 1995. Andre claims that during their US Open match in 1995, Boris was making obscene remarks and gestures to Brooke Shields and others in Andre’s reserved box at court level. I didn’t see the match when it happened but I don’t recall anything in the newspapers or on ESPN at the time about Boris doing that stuff. I also don’t recall Brooke Shields or Brad Gilbert saying anything about Boris making obscene gestures and obscene remarks to them. I tend to doubt that Boris would make an obscene gesture or obscene remark to Brooke Shields or to Brad Gilbert. I would like to hear Brad Gilbert’s take on this matter.

Andre also says that after the match ended, he let Boris stand alone at the net and would only slowly go to the net to allow Boris to feel the pain of losing and being disrespected. I watched the end of the match on youtube and Andre did let Boris stand alone at the net and when Andre shows up at the net, there is no eye contact and only a brief unfriendly handshake. But it’s not like Boris was alone at the net for an hour. The whole episode takes about 5 seconds, hardly enough time for Boris to feel the pain of loneliness.

Tennis fan in Texas · June 28, 2010 at 2:28 am

It’s amazing to me how you can be so full of knowing better what happened than people who were there at the time. Let’s see.

Becker himself confirmed what Agassi said about the summer of 1995 is correct after the book came out. But you know better than either of them!

Bolletieri said Agassi is right about how his academy was then (not now – or so he claims…).

Tarango disputes what happened in a match in the under 10s – who is to say Tarango is the truth teller there? Anyone who ever watched an intense u10 match between two very competitive kids will tell you conflict is the order of the day very often.

Pat McEnroe in his book and Bodo (who ghostwrote the tedious Sampras biography) in his column both confirm Sampras is cheap beyond cheap so the valet story seems perfectly credible. Or perhaps the three of them conspired to make that up…

Do you think he just made the fathers’ dispute up? Why would Graf let him do that?

Gilbert remains very tight with Agassi and read the book ahead of time, and I’ve heard him say repeatedly he’s happy with his part in it – but perhaps they’re both wrong about what happened between them…

Even Shields hasn’t disputed what he said – but confirmed what Agassi said repeatedly about her take – they remember the same things but interpret them differently (which by the way is the completely usual pattern for two people who are divorced looking back). I can think of one example Agassi gave in one of those hundreds of interviews – they agree they spent a lot of time apart and he felt at the time (since it’s all about how he felt at the time) that she was abandoning him and he said he thought she might say she was giving him space. That’s life between two people in a very unsuccessful relationship. For sure, if/when she writes her book, she’ll have a different version. Perhaps she loved their wedding … That doesn’t make his take wrong.

People in Vegas bet on anything – Brown and Agassi’s father making a bet in Vegas? Absolutely. Have any you guys been to Vegas?

Spadea – I’ve no doubt Agassi FELT like he should be able to beat Spadea with whatever. That’s what he’s writing about – his perspective on whatever at the time it happened.

(On a far lower scale, my daughter played – and won – her tournament last week. First match, she called me and said she played amazingly. Second match, she called and said she won ugly, not in the zone at all. My watching husband said she played identically … he was very happy with the consistency of her level. Now who was lying to me? Neither of course – they experienced the matches differently. So with many of these things in Agassi’s book.)

And so on and so on.

There’s no doubt Agassi’s father has mellowed considerably and he’s still an incredible hard you know what. He did indeed have a very tough life as a youngster and – like many many immigrants to the US – no doubt that imprinted on him, and subsequently on his family. It’s a classic immigrant family story in many regards, absolute determination, harsh discipline, children’s rebellion, second generation success and all.

Also note – he and his father are entirely reconciled. Good for them both.

Obviously it’s Agassi’s version of his experience of his life, as every biography is one person’s version – he’s been absolutely upfront about that. It doesn’t pretend to be a biography by an objective observer. (eg He means what his take on what Boris felt was … watching youtube reruns doesn’t speak to that.)

Agassi’s a very complex guy, he’s had a very complicated life, he’s done an admirable job of getting a grip on himself in the last decade plus, he’s doing something far more useful with his life, money and celebrity than most retired athletes. Sometimes life is stranger than fiction and so it’s been sometimes in Agassi’s case.

The person we haven’t heard from yet who I would like to hear from is Graf. I think she’s only said oblique things about how she loves him more than ever, and otherwise conveyed her stand by being photographed looking adoringly at him. Now she’s got an interesting story to tell. (Oh by the way I’m surprised one of you hasn’t pointed out that she isn’t in fact an angel either even though in the book he writes about her like that …) I don’t think Courier, Chang, Spadea, Gimselstob, Tarango etc can get a book deal worth anything and if they can get a book deal, they won’t sell any books (see Pat McEnroe) – but I’m very confident Graf could get one one hell of a book deal. Somehow I don’t think she’s going to take that opportunity.